Introduction

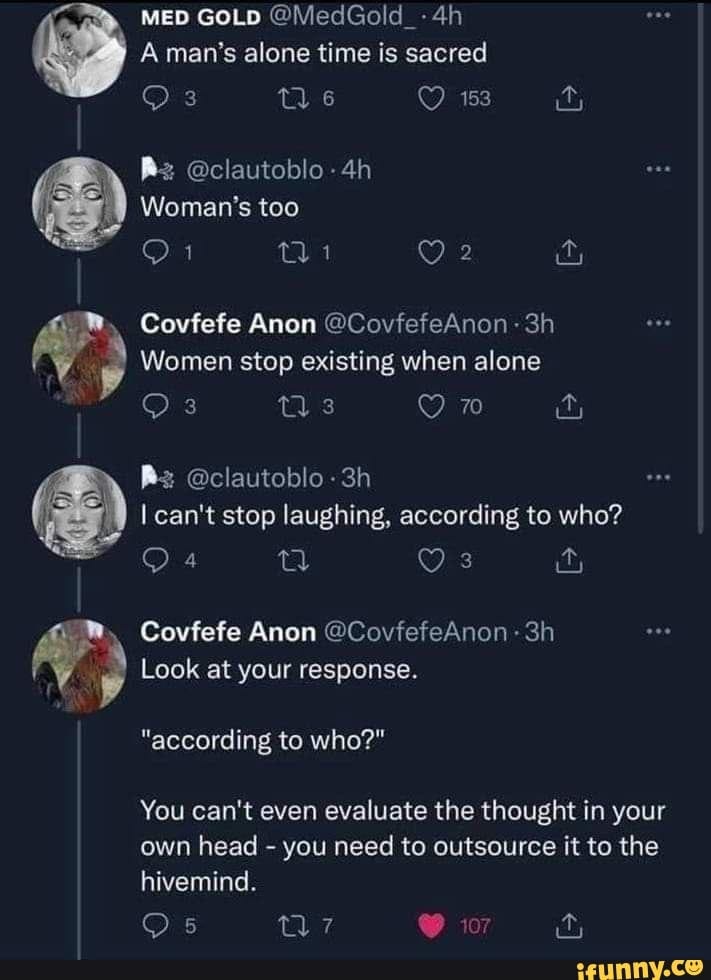

In recent years, one of the most popular meme formats is that of the NPC, the amorphous, grey-faced automaton that is supposed to represent the unwashed masses in some capacity. It’s a funny meme, and it captures something true about the way a certain contingent of the population thinks and feels. What I am going to do here is take the meme far more seriously than anyone ought to: I am going to investigate the philosophical underpinnings of a world where there are NPCs.1

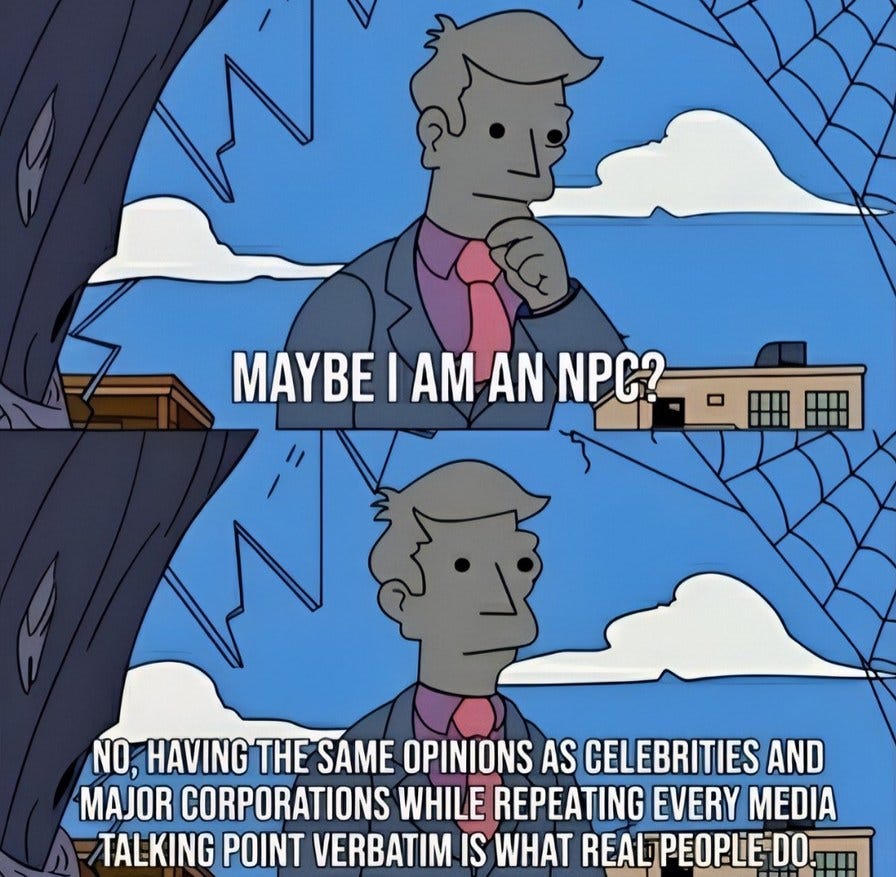

It may turn out that, in reality, there are no such NPCs. But a good way of doing philosophy—and ironically, one that so-called NPCs are simply incapable of doing—is to first think about what it would mean for x to be true, and only then see if it is true. What would it mean for there to be NPCs in the world? Perhaps there are no such beings, but we ought to at least know what we are talking about.

When I think about it, the whole problem of the NPC revolves around grounding a set of qualities in an ontological difference. Let me explain what I mean.

If we are to take the NPC meme seriously, if we assume that it captures something meaningful about reality, then the question is to figure out what this is. Now, the meme itself comes from video games, obviously. The NPC is a non-player character. The metaphysical claim here is that in the world there are two types of beings: Players—that is, beings who are somehow endowed with an active, free or spiritual personality—and then NPCs, who lack this special quality. In essence, it is the thesis that the world is comprised of humans and human beings: mere animals and persons. Put simply: NPCs are not persons.2

The view as I have presently laid it out, which is really just the simplistic thought that everybody has when they talk about this, revolves around speculative and—if I am to be honest—not altogether serious claims about the nature of reality. It seems to me that the origin of this idea had to do with a simple act of perception: namely, that a sizeable number of people (a majority?) are emotionally flat, unintrospective, low-agency, group-thinking morons—i.e., that they act like NPCs in video games. So, along with the metaphysical thesis about personhood, we have a loose bundle of qualities that are supposed to pertain to NPCs.

If NPCs really do roam the earth, then all the things we mock them for ought to be explainable in terms of an ontological difference: they are NPCs in virtue of the fact that they lack a personal center, a spiritual core, a divine spark (or what have you).

This is all quite fun, but one of the things that often happens in discussions like this is that people begin to worry that they are NPCs. The thinking goes that, well, if only a portion of human beings are persons, then perhaps I am not a person. I know a few people who, while perhaps in some sense drawn to this view, are terrified that, if true, perhaps they would be NPCs and not know it. As we shall see, ironically, it is precisely those people who worry about such a question who are at risk of actually being NPCs.

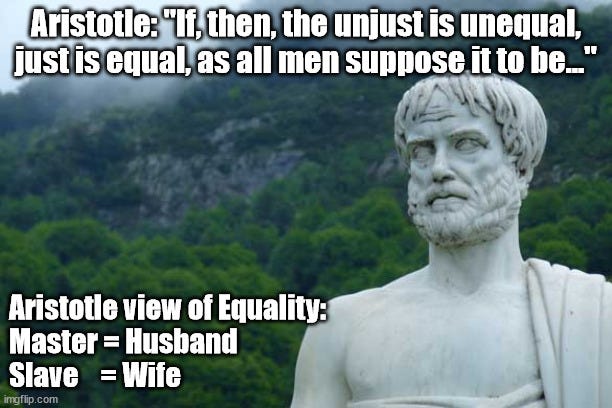

Slaves by Nature and the Rational Order

Are there any historical precedents that pertain to our present enquiry? Yes, there are. The most obvious one is Aristotle’s theory of “slaves by nature.” According to him, there are individuals who are better suited to be ruled rather than to rule. At the end of Politics, Book 1.4, we get this passage:

The master is only the master of the slave; he does not belong to him, whereas the slave is not only the slave of his master, but wholly belongs to him. Hence we see what is the nature and office of a slave; he who is by nature not his own but another’s man, is by nature a slave; and he may be said to be another’s man who, being a human being, is also a possession. And a possession may be defined as an instrument of action, separable from the possessor.

In the next section, Aristotle actually asks the question of whether there are such people, and he answers that there is “no difficulty” in answering in the affirmative: “from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others to rule.” For Aristotle, this relation between free man and slave, between those who are born free and those who are born to be subjected, is both “expedient and right.”3

But I digress. Our question is not about old theories of slavery and politics. The important part of Aristotle’s theory is his metaphysical explanation for what makes a slave by nature someone of the lower estate. I do not want to turn this into a complex (and boring) article on the nuances of Aristotelian thought, so I will take some liberties here.

Perhaps the best way of trying to clarify this is to look at Aristotle’s biomorphic view of life. Just as the human being should be ruled by his rational intellect, with the lower, non-rational parts of the soul abiding under its lawful control, so too should rational human beings rule over the non-rational. Rationality here is not only conceived of as the ability to reason things out syllogistically but is an ontological presence and power in man—nous. The slave by nature is simply unable to be rational himself and must act in submission towards another if he is to participate in the rational order. But what exactly are we talking about here?

The main distinction here is grounded in Aristotle’s theory of action, which is something so foreign to the modern mind that it is difficult to even write about. While it may seem weird to say, in Aristotle’s view action and passion are actually opposites: the wise man acts, the fool is acted upon. As I understand it, this is a genuine ontological distinction: there is a relatively autonomous form of being that exists through activity and another, more dependent form that suffers said activity’s effects. Slaves by nature (NPCs) simply are not active in the same way that free men (real people) are.

What we have here is not the presence of a subject of “player” but rather the connection to reason and a certain mode of being. To be honest, it is very difficult to actually pin Aristotle down on these questions, and the literature on this is rather confusing as well. So I apologize if this is both too obscure and not specific enough. The point is that what defines the NPC here is his lack of connection to reason, nous, or the higher parts of existence. His conformity, his lack of depth, his low agency, his use of scripted responses—all these things are explained by the fact that he is ontologically inactive. He has no ability to reason for himself and is merely acted upon by external forces.

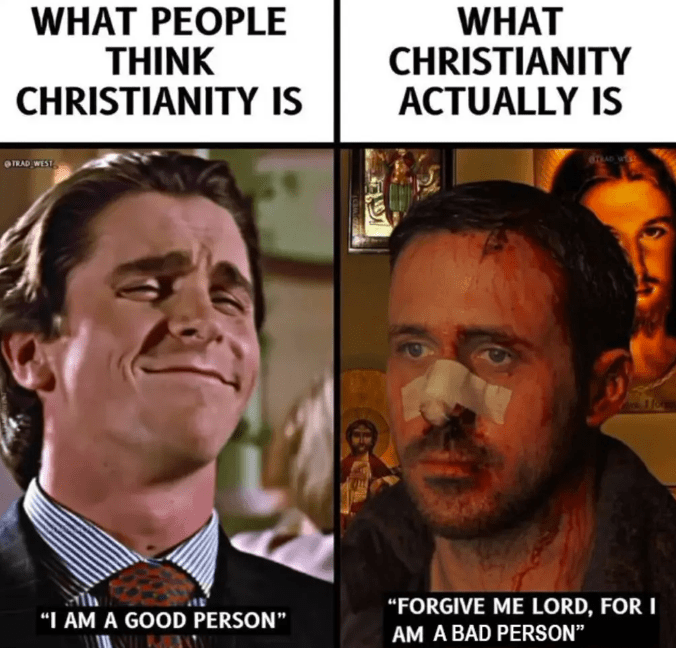

Christianity and the Reprobate

The idea of an NPC becomes ostensibly more difficult to hold within a Christian worldview, since everyone is supposed to have an immortal soul. Nevertheless, we do find suitable examples, most of which are informed by the Aristotelian view we just covered. The difference is that the aspect separating the higher from the lower changes. Instead of a distinction between free men and slaves grounded in reason, we get a division between man in a “state of nature” and man in a “state of grace.”

I am not well-versed in the Medieval and Scholastic periods, but I have read enough to see the pattern. Augustine, for example, doesn’t speak of slaves and masters but still refers to the reprobate and the elect. Consider this passage where he refers to the “dregs” of mankind:

Thus the world is like an oil press: under pressure. If you are the dregs of the oil you are carried away you are carried away into the sewer; if you are the genuine oil you remain in the vessel. But to be under pressure is inevitable. Observe the dregs, observe the oil. Pressure takes place ever through the world, as for instance through famine, war, want, inflation, indiligence, mortality, rape, avarice; such are the pressures on the poor and the worries of the states: we have evidence of them… We have found men who grumble under these pressures and who say: “Oh how bad are these Christian times!” … Thus speak the dregs of the oil which run away through the sewer; their colour is black because they blaspheme: they lack splendour. The oil has splendour. For he another sort of man is under the same pressure and friction which polishes him, for is it not the very friction which refines him? (Augustine Sermons, edition Denis, xxiv, 11.)4

This is not just a difference between those who go to heaven and those who go to hell. There is a real ontological distinction to be made here between man as an animal and man as a spiritual being, between the carnal man and the reborn man.

The Christian idea about the hierarchy of being also comes into play at this point. According to these types of views, the value of a thing is derived from being itself, so the more valuable a thing is, the more being it has—with God existing as the Summum bonum. From this perspective, NPCs literally are less than so-called real people. They exist to a lesser degree; they are further down the chain of being.5

This kind of thinking seems to have come to an end with Descartes, whose cogito ushered in a new singularism and individualism. In fact, it seems that there are fewer resources for a theory of NPCS in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries—though perhaps I am simply not well read enough. Descartes could have had a good theory of NPCs, since he believed all animals are just automatons, but his dualistic philosophy holds that all human beings are in possession of the res cogitans, the thinking substance. In Leibniz, whose views are closely related to what we have been dealing with, it could perhaps be argued that NPCs are monads with very obscure perceptions, but this is a matter by degrees, not kinds. Spinoza’s system is monistic, so there can’t be an ontological distinction here, though he too distinguishes between people who live according to their passions and those who live by reason. Kant has a theory of dignity that might be relevant, but it’s complex and not entirely relevant. Perhaps there are some other relevant views here, but I don’t know them.

In any case, there are examples of NPC-style views within the Middle Ages, and it is not clear to me that Christianity entirely rules out such positions. Some people seem to suggest that the early church adopted the principle that everyone is equally capable of being “saved” as a practical principle. In that case, the Aristotelian distinctions between free men and slaves would still hold; it would just be transposed into a religious language.6 It makes sense why such views are not held today, but I do not have all the answers here.

NPCs Can’t do Logic

It isn’t until the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century that we find more worked-out accounts of NPCdom that have some real meat on the bones. I am talking here about the crazy incel philosopher: Otto Weininger. 7

Weininger is one of the few philosophers I know of who has an account of what it means to be a non-person. The reason he has this view is because he thinks women and jews are essentially NPCs. The merits of his arguments will not be discussed here. What is of interest is his concept of “logical consciousness” and his belief that only those who can do logic are real people.

As with most commentators of his work, I am forced to begin with grotesque sexism. Weininger takes duality to be “a fundamental condition of consciousness (Sex and Character, 110) and thinks that “recognition of anything requires duality.” (92) One finds him making divisions again and again throughout the entirety of Sex and Character. In the end this principle is taken to a comically cosmic extreme when at the end of the book he describes the man/woman dyad, attributing all the positive aspects of existence to the masculine and all the negative ones to the feminine. According to him true value resides in order, clarity, harmony; in positive and therefore masculine properties. The difference between man and woman is the as between higher and lower, subject and object, logical and illogical, moral and amoral, the absolute something and absolute nothing. (297)8

This psychological distinction is projected into the cosmos at large. Thus, Weininger posits two realms of ‘being’ and ‘becoming’: there is, on the one hand, part of the universe that is in flux, time-bound and empirically contrived; and on the other there is the cold, immutable transcendence of a supra-temporal plane.

This split also manifests on the psychic sphere as two different kinds of consciousness—one mechanically bound by material laws, the other genuinely free and timeless. Weininger thinks that our experience itself is split in this way, that it is both deterministic and free, both empirical and transcendental, both timebound and eternal. There is the movement of a purely material ego (female) in spacetime and a transcendent one—for all intents and purposes, an immortal soul or spiritual personality—that sits above it all and judges (male).

Although he doesn’t say it, Weininger’s account of logical consciousness is very similar to certain Hellenistic conceptions of reason and to what we went over with Aristotle. Here, to say man is a rational animal means a great deal more for people like Weininger than it does for us; it presupposes not only the ability to think ahead and use the intellect but the existence of a transcendent dimension within the human unit, posits “the existence of an intelligible ego or a soul, as a form of being of the highest super-empirical reality.”(186)9

With that out of the way, we can now investigate what it means to actually be an NPC. On this view, an NPC is just someone who lacks this logical consciousness. They are entirely world-bound, ensconced in time and unfree. But how do you know?

The easiest test of this is logic. Weininger tells us that the ultimate principle is that of identify: A=A. He writes, “an existence has been posited; it is not the existence of the object; it must be the existence of the subject. The reality of the existence is not in the first A or the second A, but in the simultaneous identity of the two. And so the proposition A = A is no other than the proposition ‘I am.’” (157-158). He takes it to be not only a formal law, but an “existential” one as well.

It is worth pointing out here that the term “logic” here does not refer to our current quasi-mathematical study of inferences. In Weininger’s time, it was a study of judgment (Kantian stuff). Weininger is not suggesting that NPCs can’t solve proofs; what he argues for is that such people do not feel them to be true. They merely carry out operations like a computer. A real man, a player, someone with higher consciousness, knows the truth of a proposition through “affective perception,” which is a fancy philosophical way of saying “he feels that it must be true” or “he feels its truth.”10

The NPC, when presented with even the most obvious logical proof, lacks this feeling. He may perform the operations because the laws say he should, but the access to these laws is forever outside of him. This explains why NPCs sometimes have a difficult time understanding how a movie can be bad despite making lots of money, or why they might think that we can just redesign foundational concepts—even something like mathematics—however we want. They do not feel the law; they do not see the timeless principles that underly our world. They always require something external to themselves. Like Aristotle writes, they do not act but are acted upon.

So, reader, do you think that A = A, necessarily? Can you see why 1 + 1 = 2? Or do you need an expert to provide you with a proof?

Nobility and Self-Value

The final thinker I’ll mention here is Scheler, whose theory of self-value is probably the best example for showing which kinds of people definitely aren’t NPCs. In Scheler’s case, rather than breaking things down along gendered lines, we have a distinction between the noble and the common.

Scheler thinks that one way of distinguishing the two is by how they apprehend their own self-value. The common person always experiences his value in relation to others, either as “above” or “below”. The noble person, however, experiences his value prior to any such comparisons:

The attitude which Simmel calls “nobility” is distinguished by the fact that the comparison of values, the “measuring” of my own value as against that of another person, is never the constitutive precondition for apprehending either. Moreover, the values are always apprehended in their entirety, not only in certain selected aspects. The “noble person” has a completely naive and non-reflective awareness of his own value and of his fullness of being, an obscure conviction which enriches every conscious moment of his existence, as if he were autonomously rooted in the universe. This should not be mistaken for “pride.” Quite on the contrary, pride results from an experienced diminution of this “naive” self-confidence. It is a way of “holding on” to one‟s value, of seizing and “preserving” it deliberately. The noble man‟s naive self-confidence, which is as natural to him as tension is to the muscles, permits him calmly to assimilate the merits of others in all the fullness of their substance and configuration. (Ressentiment, 16)

This kind of difference isn’t a theoretical thing like we saw with Aristotle, though Scheler probably has something like that in mind lurking in the background; nor is it a matter of silly optimism or an appeal to one’s intrinsic value as a child of god. It’s a change in attitude and perception of oneself: it is a difference in how you feel. The NPC cannot feel his own value independently from other people; the noble person, on the other hand, has a kind of direct feeling for his own self-worth.

With that said, I don’t believe the common man is necessarily an NPC. When I think about this idea, I would reverse the formula: if you’re noble and perceive your own self-value, then you are not an NPC11. But the opposite does not seem to be the case, as there are plenty of people who are sensitive to such things but who I believe are “real.”12

The Schelerian perspective also brings a couple more important points to bear. We can’t cover all of them here, but the idea of failing to distinguish yourself from the world seems salient. In the final section of his book, The Nature of Sympathy, Scheler describes the conscious experience of a baby:

in the early stages of infancy, our mental pattern corresponds to that which must also be ascribed to the herd, the horde and the mob; for at that time we absorbed unconsciously, by means of true identification and a genuine 'tradition', certain contents and functions of other minds… (The Nature of Sympathy, 228)

Viewed from this perspective, the NPC is rather like a perpetual child, someone who unconsciously absorbs the thoughts and feelings of those around them and takes them for their own. He does not think; he mistakes the actions around him for his thoughts. From this perspective, we were all NPCs at some point: when we were kids. Scheler tells us as much near the end of The Idols of Self Knowledge when he writes,

One’s own experiences are, at first, completely veiled from inner perception by the alien experiences which rest on shared action, vicarious sensation, and ciacrious feeling, by experiences which are given to us, though an illusion, ‘as our own.’” (Selected Essays, 89)

The idea seems to be that, if there is a self, a personal center—something we could call a “player”—then it is initially occulted. One must tear away the veil of all that is imposed by society so as to eventually reveal the presence of this higher power, which when realized and integrated, leads to new ways of interacting with the world and to new ways of feeling.

This topic is broad and deep, so I will end it here. Curious readers should read the final section of The Nature of Sympathy and The Idols of Self-knowledge—or tell me they want more in the comments and I’ll write about it.

A good rule would be this: If you are constantly worried about what others think of you, if you only want what other people want because they want, and if you feel better about yourself when other people fail; then you’re probably an NPC.

Conclusions

So, what do we say in the end? None of this is meant to be definitive, but I hope it has shed some light on this issue.

If we look at the NPC from a historical standpoint, we find that it differs from our modern, videogame-informed perspective, which holds that the NPC lacks a “player.” We now have several different ways of explaining this:

The NPC is irrational and passive (Aristotle).

The NPC is relegated to an animal and cut off from God (Christianity).

The NPC lacks access to some special kind of consciousness (Weininger).

The NPC is wrapped up in his surroundings and does not know himself (Scheler).

I am sure if I worked harder, I could find more examples. But I trust that the reader understands the kinds of avenues that are available—and perhaps even has an idea of what others may be available. The point is that the NPC is cut off from the higher parts of mental life. How you want to cash that out is up to you.

Viewed in this light, we can now explain how the traits that are common to the NPC—scripted responses, lack of introspection, low agency, groupthink, et cetera—come to be. Without access to reason, with no connection to the divine, with no transcendental ego, and without a self, he is left with only the world.

In some sense, the NPC just is the world: he has a dependent existence and has no ideas or thoughts or feelings that could possibly be ascribed to himself.

It could be argued that the promise of religion and the purpose (of some conceptions) of philosophy is to bring the individual out of NPCdom: to become a real individual, a child of god, perhaps even a kind of tiny god (a microcosm that reflects the whole). So, if you fear you might be an NPC, then don’t worry. There is still hope for you.

And of course, everything here is highly contentious and by no means obviously true. Even the positive accounts I’ve given conflict with each other. But like I said at the beginning: before deciding whether x is true, we ought to first figure out what x is. I hope you at least have some idea now.

Also, if this post makes you afraid or angry, well, let me just say that’s not a good sign.

This is one of the joys of knowing a decent amount of philosophy. What is the point of knowing a few things about the history of ideas if you can’t use them for your own amusement?

Note: I will not be addressing the ethical implications of this view here; I simply don’t care.

The legal inequality between slaves and masters on this view is not the result of equal natural rights being “corrupted” by power relations, but is instead the expression of the natural differences between men, with rational ruling over the irrational.

I found this lovely quote at the beginning of Karl Löwith’s wonderful book, The Meaning in History.

Scheler talks about this somewhere in Problems of a Sociology of Knowledge.

Scheler seems to have such a view: “The idea that each human being has a “spiritual, rational, immortal soul” with equal potentialities, equal claims for salvation, or even equal “abilities” or “innate ideas,” and that by virtue of this fact alone without “grace,” “revelation,” “rebirth” man is essentially superior to the animal and to the rest of nature—this whole notion was added to Christian ideology at an early date, but has not grown from its living roots. It is originally introduced not as a “truth,” but as a mere pragmatic-pedagogic assumption, indispensable for rendering missionary work possible and meaningful. For exactly the same reason, ancient logic and dialectics— first rejected as “diabolical”—became the chief subjects of instruction in ecclesiastical philosophy. In order to reconcile his doctrine of grace with his priestly practice, Augustine writes that nobody can know whether a person is an “elect” or a “reprobate,” neither he himself nor any priest, so that the practical priest must treat every man “as if” he were not a reprobate. But though originally a pedagogic and pragmatic assumption, the doctrine of the equality of human nature lays more and more claim to being considered as a metaphysical truth” (Ressentiment, p 85-86)

It ends up being quite difficult to find people who actually defend NPC-style views. It could be that such views are more common and that they’re merely forgotten or ignored (with Aristotle being the exception because, well, he’s Aristotle). Weininger isn’t really read at all these days except for by hardcore sexists, which is a shame because he has some cool ideas. One wonders how many other such people have been expunged from the philosophical record—or how many popular philosophers have had their true views obscured.

This kind of view is very clearly wrong. But I will not go into that here. Dimitry’s recent articles on masculine and feminine values actually express what I take to be the correct view.

This thesis is not particular to Western traditions, and one finds something like it across many different cultures from both East and West. Students of philosophy will note the similarities here with the Greek noesis, but I want to stress just how widespread this kind of view is from a historical perspective. To take but a single, popular example, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra—itself more than 2000 years old—essentially makes Weininger’s distinction between psychological and logical consciousness, between mental and psychological. The translator Chip Hartranft has this to say regarding the doctrine: “consciousness and pure awareness underlying it are separate but generally feel like the same thing.” (The Yoga Sutra, 1) This “awareness” is almost conceptually identical to Weininger’s logical consciousness. The Sanskrit term is Isvara, which in the 24th sutra is defined as “a distinct incorruptible form of pure awareness, utterly distinct from cause and effect and lacking any store of latent impressions.” Like logical consciousness, Isvara is conceived of in transcendental terms as being that which is beyond space and time.

This is a view that is not common, but we find it in Pascal, in Nietzsche (sort of), in Scheler, and finally in Sartre. There are others who defend this, too. It is a fascinating topic. For Weininger this also applies to the moral law.

I think it follows that a noble person of this kind would not worry about being an NPC because he perceives his own value.

I won’t argue for this here.

I'm gonna trust everything you said. Thank you for providing some external validation for my preconceived notions on the different levels of being.

Such excellent writing, thank you.