Nietzsche and The Heroic Instinct

On asceticism and the possibility of a "spiritual vitalism"

The concept of “the hero” has been a pet project of mine for many years now. I will write many more essays on this interesting topic, but here I consider whether there might be a “heroic instinct.” I know many people have an interest in Nietzsche these days, so I decided to frame the topic in Nietzschean terms. This is part of a larger series I am doing on (g)nobility. All links to other articles will be included at the end.

§1 Nietzsche and Asceticism

Nietzsche’s third essay of the Genealogy of Morals is one of the greatest philosophical essays ever written. In it he presents his critique the ascetic ideal, which is something of a lynchpin for his entire project. It is here that he attacks the foundation of all religious spirituality and philosophical speculation: the idea of vital repression, of self-discipline in the service of a higher purpose—which for Nietzsche is ultimately nothing. This is the traditional path towards metaphysical human meaning, something he seeks to reject and replace. Throughout the essay Nietzsche considers a number of different cases, since the ascetic ideal means different things to different people: for the philosopher it is a way of procuring the most favorable conditions for his mental flourishing; for the bulk of mankind (“the physiologically deformed and deranged”) it is a way of coping with their inferiority; for the priest it is a means toward worldly power; and for the saint it is pretext for self-annihilation.1

Although I have read this essay many times now (and loved it for years), I have always had reservations that there was something I didn’t agree with. I have my breaks with Nietzsche more broadly, but I think it is useful to try and frame all disagreements in a similar language so as to avoid misunderstandings. After much thinking, I believe I have figured it out.

The central claim of this essay is that, (1) despite the breadth and originality of his critique, Nietzsche never manages to attack, or even so much as recognize, the essential meaning that asceticism has for the highest kind of man, and that (2) asceticism of this sort does not contradict the Nietzschean imperative of saying “Yes!” to becoming; it merely goes beyond Nietzsche’s anti-metaphysical perspective.

Thus, the third essay of the Genealogy of Morals constitutes a new descriptive account of the phenomenon—or to be more precise, a set of such accounts—but in no way can this be taken as a decisive rebuttal of the ascetic ideal. As we shall see, what I have termed “genuine asceticism” is grounded in exactly what Nietzsche thinks all positive actions are grounded in: healthy instincts, specifically, a very particular kind of instinct whose content cannot be easily explained by either Will to Power, natural selection or any other biological imperative—a “heroic instinct.”

If there is such a thing as this “heroic instinct,” then a part of Nietzsche’s philosophical project rests on an error—namely, the error of of conflating Becoming with mere life—and the true meaning of the ascetic ideal, in its most perfect form, is not a denial of life nor a peculiar expression of it, but a path towards a new kind of existence: a genuine vita metaphysica.

Philosophical Asceticism

If we ignore the analysis of artistic expressions of asceticism and its presence in women at the beginning of the essay, then Nietzsche’s critique consists of two parts: a positive evaluation and a negative one; an analysis of what we might term “philosophical asceticism” and “priestly asceticism.” As I’m really interested in the positive conceptions of asceticism, I’ll bracket my summary to the philosophical one.

For Nietzsche, the positive form asceticism has nothing to do with traditional ideas of “taming” instincts by force of will (which, for him, is an illusion anyways) but rather consists in having one particularly powerful instinct,2 a desire for philosophizing and mental activity, which requires that an individual curtails his other drives so as to actualize its fullest expression. Asceticism here is just the natural result of physiology: the philosopher ostensible “virtues” are merely the expression of his dominant instinct prevailing against less important drives. They’re the result of being biologically healthy. If the philosopher does subject himself to more severe forms of deprivation, then this is explained as a means by which to go beyond inherited valuations that oppose his own instinctual nature and as a consequence of the brutal ages in which these men lived.3

On such a view, there is no solemn renunciation of sensuality but rather an easy, natural restriction of it: chastity is useful because sexuality can overpower the contemplative man.4 Likewise, solitude is necessary to get away from the masses who make man mediocre through osmosis; marriage causes problems; he who owns things is owned by them; et cetera.

But these practices are valid only because the philosopher is a particular kind of man existing in a particular social milieu: they are valued for their utility. There is nothing essentially meaningful or valuable about asceticism as such, and it is only contingently useful as a way of realizing other goals.5

On Nietzsche’s view, therefore, the philosopher never raises himself into metaphysical height through his solitary, “desertlike” existence; he merely brings about the most perfect development of a rather rare drive for mental activity through the elimination of everything that could distract him from it. Furthermore, this austerity is not even a necessary condition, and Nietzsche tells us that a large part of this need for solitude is based on the fact that the rest of humanity, the herd, is suspicious of all that goes against convention—a state of affairs which made it necessary for the philosopher to adopt the image of the priest as “mask” or “cocoon.” This means that in a better world, a world congenial to so-called free spirits perhaps, asceticism itself may no longer be needed at all.6

In the end the philosopher remains an animal among other animals—a cold, hard, noble beast who yearns for clean air and freedom from the masses.

The Meaning of Ascesis

Now that we have a basic view of Nietzsche’s positive account of the ascetic ideal we can contrast it against the concept as it was traditionally understood in its most wholesome forms. Metaphysically, an essential feature of almost all positive forms of ascesis (that I know of) is the presence of a “higher principle” within the human being, of something which is beyond mere life.7

The original meaning of ascesis simply means "training,” and the Indo-Aryan term tapas (tapa or tapo in Pāli) has a similar meaning, with the root tap- also meaning "to be hot" or "to glow." Consider the metaphor of finding a needle in a haystack: the best way to find it is to set the whole thing on fire, to destroy all that can be destroyed by flame.8 This “training,” therefore, is simply a method of strengthening this connection to a spiritual power and anchoring oneself in it; it is a training for “liberation” or sometimes even a deification.

Those are broader theoretical characteristics of ascesis, but we also ought to consider its essential nature from a psychological standpoint. All asceticism presupposes the renunciation of striving after a positive value. The ascetic voluntarily “gives up” pleasure, comfort and sometimes even his own health, among other things. But the nature of this renunciation can take a number of different forms:

The positive value is given up “for nothing.” This idea is at the core of Nietzsche’s critique of all negative forms of ascesis—or what I will call pseudo-ascesis. In this case, the value is rejected for deontic reasons. God commands that you give x up; it is your duty to stop striving after x. The person renounces something valuable, like health, because it is commanded of them or because of an intellectual “theory” which stipulates such renunciations.

The positive value is given up in place of another. This is essentially what happens with Nietzsche’s philosopher. But in some sense, this isn’t really asceticism: it’s just the sacrifice of one value for another. Although it may look similar from an outside perspective, the reason for the renunciation is that x and y cannot be co-realized, and the person gives up x in his pursuit of y, either because the latter is a higher value or because it is the object of a more dominant instinct.

The positive value is given up because the act of renunciation is felt as good in its execution. This is similar to the first case except for the fact that the motivation for the act cannot be understood as any kind of duty or command. Here the positive value is given up “for nothing,” but this just means that the person has no object in mind when he refuses to strive after x. Somehow or other, a positive value is given in the act of renunciation itself without being striven after deliberately. This is a much more complicated—and relatively widespread—thesis that the highest things in life cannot be willed at all and can only be acquired by “the grace of God” somehow.9

These three forms of renunciation correspond, accordingly, to (1) pseudo-asceticism, (2) ascetic sacrifices and (3) genuine asceticism. Only the first and third are compatible with traditional ascetic practices; the second, while ostensibly appearing like asceticism, is really just when someone pursues certain values at the expense of others.

It is also important that the “higher principle” presupposed by all forms of spiritual ascesis has something of a negative quality about it, which Nietzsche rightly notices. There is no shortage of this idea in the history of religion (nirvana, apophatic theology, …). In pseudo-asceticism this absence is purely formal, and Nietzsche rightly critiques the cadaverous quality of such practices. They require that the person submit to a law or perform his duty, which for someone like Nietzsche is ultimately explained by the instinct of declining life. In this sense, pseudo-asceticism is purely deontic: it concerns empty theories, false laws and “thou shalts.”

With genuine asceticism, however, the case is quite different. The “nothingness” in these acts is not the result of an empty law but of the fact that the higher value cannot be an object of the will. We cannot try to realize it in any meaningful way.10 Such practices, although perhaps codified in formal rituals, ultimately have their ground in the feeling for value—in the “instincts”—and they are not derived from a formal ought.

Genuine asceticism is also “supererogatory,” which is a fancy way of describing something that goes above and beyond the call of duty. It’s not something everyone ought to do, but it is a very good thing. It’s not required that you be polite, but it is good. It is not required that you risk your life to save another, but it is good. Unlike pseudo-asceticism, which is driven by deontic concepts, genuine asceticism also proceeds from a feeling for values. The true ascetic feels that his practice is good even if there is no object he is striving to attain and his actions are purely negative. In the absence of this feeling for values such practices are prima facie impossible

§2 The Essence of Heroism

Traditional Heroism

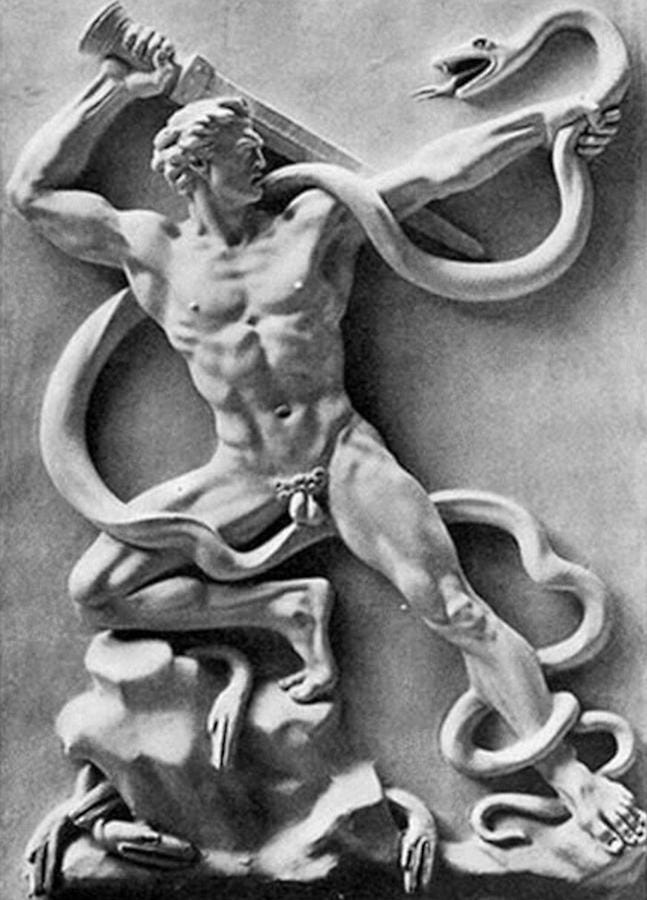

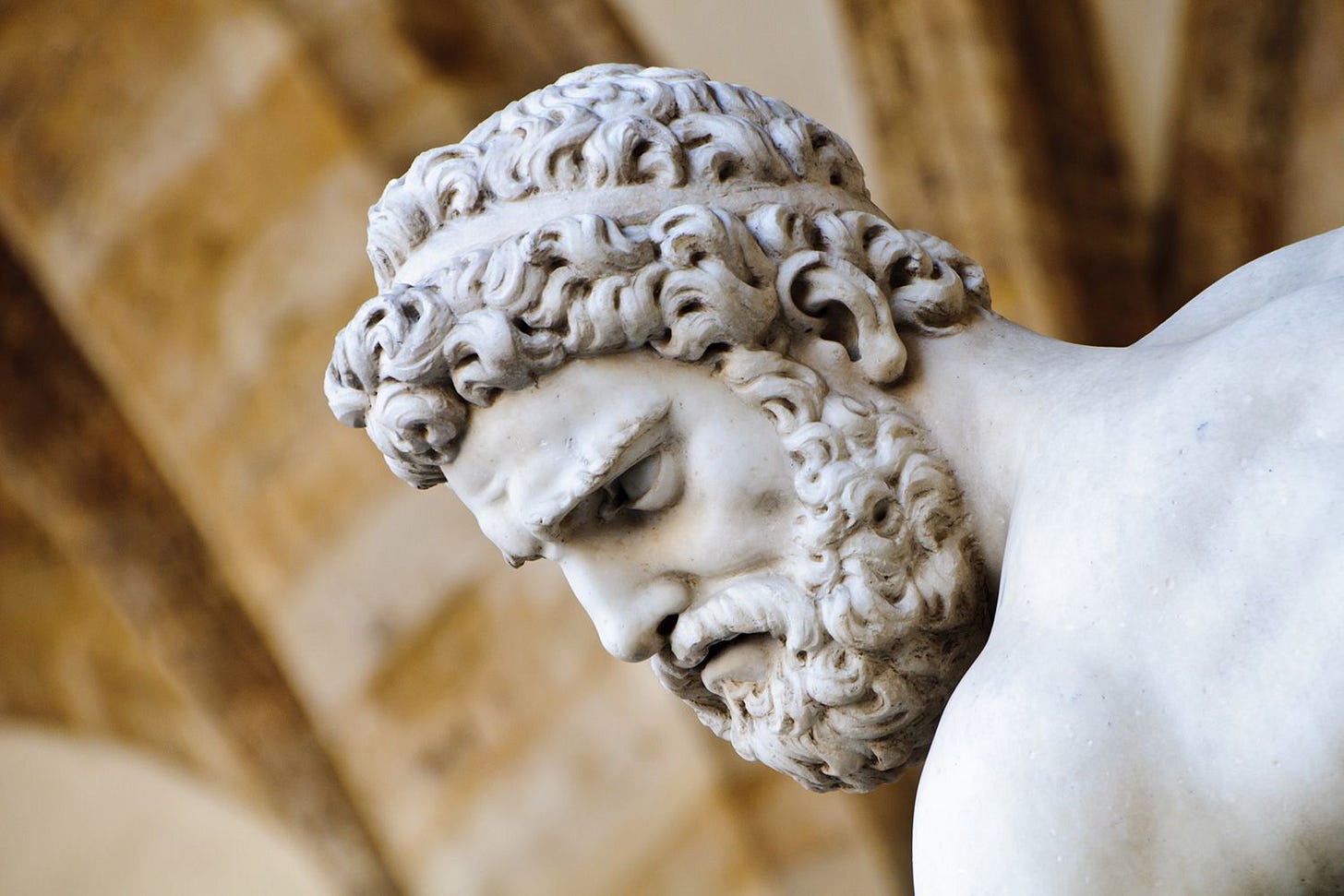

Also related to genuine ascesis is the concept of “the hero.” The hero is traditionally conceived of as a demi-god who must overcome some worldly quest in order to win his immortality. We find this in both East and West. Older Orphic myths refer to a kind of Olympian immortality wherein the heroes attain literal eternal life after death. Hesiod refers to the Elysian fields and so too does Homer. One can think of Hercules’ trials, of Jason’s pursuit of the golden fleece, etc...11 In the East these types of myths are also prevalent, with the Bhagavat Gita being the most perfect expression of heroic conquest.

But what do these myths mean? The most relevant interpretation for our purposes is the idea of the hero as the transcendent will fighting to overcome the “monsters” of the earth, which is to say, of drives. The external combat is merely a pretense for an inner transfiguration. Along with monsters the hero must fight his drive for self-preservation, his petty wants and desires—that is, everything coinciding with mere life: his own drives. This is the quest he must embark upon.12

In some sense genuine asceiticism is a species of heroism. The distinction between the hero and the ascetic (even if it be inconsequential in the larger scheme of things) is one of orientation towards the world: the hero is extroverted whereas the ascetic is introverted. At base, however, both are essentially engaged in the same project, on the same quest. The difference lies in the way the realization is achieved.

The heroic path is suited towards those who are more powerful in the Nietzschean sense, more physically robust, that is. They seek out danger, adventure, experience, with the hope of finding something permanent within themselves. Even war can be used as a means to purify oneself, as a means of overcoming the lower instincts.13 He conquers the external world in an effort to achieve inner liberation.14

The ascetic is essentially the hero who has turned his gaze inward. Rather than fight in an external conflict, which may be impossible due to physical disabilities or political circumstances. Nietzsche rightly infers this when he writes about the warlike man’s tendency to fight himself in the absence of genuine conflict—though his analysis lacks the underlying idea of heroic transfiguration.

The hero dominates himself through his conquest of reality; the ascetic does it through introspective self-denial and self-mastery. The former uses external world as a means by which to subjugate his lower drives; the latter “combats” the drives themselves through deprivation. In both cases the goal is to bring the mind (and body) under the lawful rule of something higher. This is why many traditions use regal symbolism: the spiritual king ruling over the kingdom of the body.

But there are a few different kinds of heroism that need to be distinguished.

Apollonian Heroism

An Apollonian heroism is designated by a formal imperative and corresponds to pseudo-asceticism. It’s about “duties.” The Apollonian hero, having been convinced either through rational arguments or religious faith, holds that there is something divine within him. The nature of this thing, however, remains forever foreign to him; it is beyond, unknowable, mysterious. At bottom all he has is a formal principle: overcome your drives.

The issue here is that there is no dominant instinct, to use the Nietzschean term, driving this action and no intuitable justification for it. He is merely “going through the motions.” We often find similar people today who are obsessed with productivity and “self-improvement.” The imperative is there, but it is given as a kind of absolute command from on high. It isn’t clear at all why we ought to do this—or if it is, the answer is given in purely dialectical terms.

This kind of Apollonian heroism, whatever its form, requires faith in some abstract idea for its validity. While it may not always be grounded in the phenomenon of ressentiment, such a view lacks any direct connection to the emotional life. The Apollonian hero combats his drives simply because he is commanded to do so. The “death of God” (taken here as the skeptical denial of all transcendent grounds) would utterly undermine this kind of practice because it obliterates the one giving the command.

The question as to whether Apollonian heroism and its corresponding ascetic practices can lead to a better life is irrelevant on this point. In the end, like pseudo-asceticism, it relies on purely deontic concepts, on the belief in a purely formal law, one whose ultimate ground is forever beyond us and must be taken on faith or reasoned into dialectically. Nietzsche rejects this, obviously, and I think we would be wise to do so as well.

Dionysian (or Nietzschean) Heroism

Nietzsche breaks yet again from more traditional views and takes the tragic hero as his ideal. Moreover, he has a very idiosyncratic understanding of tragedy. The theme takes on for him something much greater than it does in other writers. It is an obsession that consumed him throughout his life, a personal theme: his first book is The Birth of Tragedy; he writes about the topic from the beginning to the end of his career; and he ends both books IV and V of the Gay Science, as well as Twilight of Idols, on this note.15

Within Nietzsche’s metaphysics there is no “higher principle” (once we get to Human, All too Human) that can restrict or condition the animal instincts because Becoming simply is life and life is will to power. Traditional heroism promises the attainment of a fullness and meaning which is of a different order than that of life; Nietzschean heroism is a kind of absolute intensification of life.16 We could call this “Dionysian heroism.” The difference here is not purely metaphysical either; it has real consequences for the kinds of states that correspond to heroism, too.

Traditional heroism is detached, calm, lucid; Dionysian heroism is a kind of depersonalized, orgiastic manifestation of primal chaos, of the Will to Power itself. The whole point of the tragic hero is that he fails to attain his goal. In Aristotle’s Poetics the tragedy is supposed to inspire pity and fear; more importantly, the result of the tragedy hinges on a mistake. (1452a 15) For Nietzsche the traditional heroic quest is a metaphysical impossibility, and his work here can be interpreted as a way of finding the meaning in failure, the meaning in pure life—in what he terms “the tragic feeling,” which is sometimes written about as though it were of absolute value.

This is a very interesting and complicated topic, but I will just mention it here. The ending of Twilight of the Idols is representative:

Saying Yes to life even in its strangest and most painful episodes, the will to life rejoicing in its own inexhaustible of its greatest heros — that is what I called Dionysian, that is what I guessed to be the bridge to the psychology of the tragic poet. Not in order to be liberated from terror and pity, not in order to purge oneself of a dangerous affect by its vehement discharge — which is how Aristotle understood tragedy — but in order to celebrate oneself the eternal joy of becoming, beyond all terror and pity — that tragic joy included even joy in destruction.

The True Ground of Heroism

What then are we to make of Nietzsche’s critique of the ascetic ideal, as laid out in the third essay of the Genealogy of Morals? At best we can say that he offers us a novel descriptive account of the phenomenon from an anti-metaphysical perspective. Instead of the ascetic bringing his passions under the lawful accordance of spiritual powers (which is in line with the traditional views on virtue), we get someone (the philosopher) whose sensual instincts are dominated by an especially rare manifestation of the will to power. Instead of a method for reaching liberation from the vital sphere, we get the sick man’s tool for gaining temporal power. Both these accounts are interesting, and both are correct from a certain point of view. Neither, however, takes aim at the traditional, positive forms of ascesis—the heroic, noble pursuit of something beyond life—that I have elucidated out here. A genuine “takedown” of the ascetic ideal should at least have mentioned this possibility.

What Nietzsche misses is the idea that ascesis could be grounded in a special kind of instinct which differs categorically from all others: the heroic instinct to overcome life itself.

Ontologically speaking, such an idea is impossible for him, for he has no notion of something beyond life; but it is strange that he does not consider, even on a purely descriptive level, the kind of heroic, self-sacrificing actions that have driven so many men—from both East and West—to “combat” life through ascesis and external conquest. In this respect, I think we can say that he misunderstood asceticism—or at least this peculiar version of it. But I may be wrong here.17 The next question is whether the belief in this heroic instinct is at all tenable for those of us in a post-Nietzschean world, and what it would mean.

§3 The Heroic Instinct

The basic theme of this section concerns the nature of what I have termed the “heroic instinct.” This is not a term we find in Nietzsche’s writings, nor in any other philosopher so far as I know, but the ideas here are derivative from many different religious and philosophical perspectives—all of which held that there was something in man which was of divine or supernatural origin.

The purpose of this is not to offer an argumentative defense of this idea but merely to give it a clear presentation. It may well be that there is no such thing—but a good way of doing philosophy is to define “what it would mean for x to be the case” before answering the question whether x is the case. Otherwise, we are led into all kinds of superfluous arguments and disorienting tangents. It is also important to place these concepts within the present framework: the details of concepts like the atman or nous, while relevant, would only serve to obfuscate the basic point, even though they are related to what I am expressing here.

Feeling as Definition

In Wallace Steven’s great poem, Examination of the Hero in a Time of War, we get the following lines:

It is not an image. It is a feeling. There is no image of the hero. There is no image of the hero.

Now, of course, we already defined the hero in metaphysical terms earlier, but what differentiates the conception of the hero I laid out there from Apollonian heroism is the felt presence of an instinct towards self-mastery. This is different from Nietzsche’s ascetic philosopher, whose dominant instinct for the contemplative life requires certain sacrifices (some of which are contingent on his social millieu); here the instinct itself demands said sacrifices. One might have a desire for food or sex or social interaction, but the heroic instinct desires nothing: it’s object is purely negative. To deny drives, to conquer oneself—that’s it. This is the seed from which all genuine asceticism can grow.

Here any theoretical explanations are utterly superfluous: one is only aware of the deep need to take ownership of body and mind, to dominate oneself.18 From the viewpoint of practical philosophy, such a phenomenon is explained in terms of “values,” not “oughts.” The hero feels drawn, pulled, attracted, and interested in self-denial. It is felt as good even if the nature of this good is not immediately known.

This is remarkably difficult to interpret this drive in Nietzshcean terms, for it seems an instance of “life against life,” which is “physiologically considered and not merely psychologically, a simply absurdity.” (GM, III, 13) The issue is that this is a case where the instinct itself is oriented towards the subjugation of all other instincts. To the heroic man this is an obvious case of preferring the higher to the lower, but from the perspective of power—even power as it is conceived of by Nietzsche—it is an enigma. To subject oneself to pain for no discernable reason, to abstain from fulfilling any instinct whatsoever, to make no art, conquer no territories, experience no positive states of vital exuberance—this is a truly perplexing phenomenon. How could it be healthy?

The answer is that such practices are valuable in non-vital ways. Nietzsche’s whole philosophy is orientated towards life and vital values, so it’s natural that such behaviours would perplex him. He correctly infers that self-consciousness makes man “weaker” but fails to see (or believe) that this might lead to something of even higher value, to something which is above biological reality entirely.

One could hold that this kind of urge is merely a delusion or an unconscious expression of priestly control, but I find such explanations unsatisfying. The fact of the matter is that, for those who lack this instinct for self-possession, the underlying reason here is completely inscrutable—and this is exactly what Nietzsche says in the second entry of the Gay Science when he describes the relation between the vulgar and the noble.

The fact is that a heroic instinct is a noble one, and as such, its value is completely incomprehensible to the vulgar person. As such, it’s also a part of the biologically well-constituted by definition.

Regardless of the metaphysical implications, this instinct is just as real as it is incomprehensible to many others, especially women.19 The desire to run until you piss blood, the need to arbitrarily starve for a few days to “see if you can,” the heroic dream of dying in combat or sacrificing oneself in a dramatic fashion—all of these are experienced as authentic manifestations of one’s own becoming.

Even if we dispense with the idea of any metaphysical ground for such instincts, which can only be postulated after the fact, the deep need for self-denial remains as an essential part of many people. And it is not clear to me that this is necessarily the result of declining life, as many people who yearn for this kind of thing are those in possession of vitality in a high degree. Nor is it clear how it is that someone like Nietzsche can easily reduce such actions to a principle like Will to Power.

On Spiritual Evolution

I will now present you with the key thesis for those who wish to break with Nietzsche without rejecting him outright. The idea is that Becoming cannot be reduced to life and the will the power, that there must be something within the human being’s becoming which is ontologically distinct from life. We might conceivably designate such a view by the contradictory term “spiritual vitalism,” but I think it’s probably not far off from what Aristotle thought.

This does not involve a denial of becoming and cannot be explained as a “wrong turn” in any Nietzschean sense. The claim is that Becoming itself cannot be fully understood in vitalist terms (which is similar to the vitalist thesis that the laws of biology cannot be reduced to those of chemistry). If one is to say “yes” to becoming, which is Nietzsche’s most important imperative, there comes a point where we must say “Yes” to something which is beyond life and therefore say “No” to all that came before. This is a reversal from a vitalistic standpoint, but if Becoming encompasses something more than mere life, then this ascetic denial constitutes the proper, healthy attitude of maturation.

Nietzsche can’t go in for this because he often walks a more positivistic line. I know we can’t pin him down in this respect, but I can’t think of any passages that are compatible with such a view—and there are many that are not. Nietzsche is obsessed with vital values, with life and strength and power. What we have here is something that goes beyond these things, though it doesn’t designate them as negative in any way. But it is “higher.”

Such a position breezes through the bulk of Nietzsche’s most viscious attacks completely unscathed. The ascetic ideal, the pursuit of “nothing,” is in its authentic form a desire to overcome life itself: to reach a state beyond that of the physical organism—a purely spiritual mode of existence.20 It’s a healthy, positive, natural thing.

Thus, the hero (and ascetic) can be said to move from mere physical life to a greater form of “spiritual” or “mental” life that is unconditioned by psychophysical laws, which fits the idea that the hero is after immortality, spiritual life: a vita metaphysica.

This is not my idea either. The type of view I have just outlined grew out of early 20th century German philosophy. During this time, there was an attempt to reconcile traditional philosophy with Nietzschean relativism. The result was that man’s spiritual life lost its fixity.

In Plato’s heaven, the forms exist as enduring objects beyond space and time; in traditional Christian doctrine, God is unchangeable. Old views like this hold that the spiritual life is grounded in the immutable. If you believe Nietzsche’s attacks succeed, this is wrong. Because nothing is fixed.

There are, then, two ways you can proceed: either you deny the existence of anything mental or spiritual (which is what Nietzsche does) or you hold that reason itself grows—and perhaps that it even grows out of life.21

If you go in for the second of these options, then a “heroic instinct” could be what Nature (in the old sense) uses to create a being who is not bound by biology. I do not see how Nietzsche could conceivably hold such a position, and it seems that his only option would be to redescribe the entire phenomenon (which I don’t think is in GM III) in vital terms.

But these are very complicated topics, so I will not say more here. Two books are worth mentioning, however. Max Scheler’s short The Human Place in the Cosmos and Helmuth Plessner’s Levels of Organic Life and the Human. Both of these were published nearly a hundred years ago (1929), and although they treat similar subject matter and write from a similar tradition, they are independent.22 Cassirer also has a short essay on the topic called “Spirit” and “Life” in Contemporary Philosophy (1930), which can be found in the third volume of his Philosophy of Symbolic Forms (Routledge). But it seems like this whole idea died in the 20th century because naturalism became the dominant trend in analytic philosophy and retardation became the dominant trend in France.23

If you take this sort of thing seriously, then you get the best of both worlds, so to speak. There is a big focus on vitality, on personal growth, and on all the things that appeal to many modern-day vitalists; and you also get access to (possibly) all the principles that have been the subject of traditional philosophy—intentionality, free will, morality. For such a view, genuine asceticism represents a new step in the ladder of becoming: an inversion, a looking inward, a liberation—and perhaps even the dawning of philosophy and a knowledge of the world’s essential structure.

Time will tell whether such a view ever becomes popular again, but I for one find this kind of thing very enticing.

The (g)Nobility Series

See GM, III, 1. Note that in this passage, as well as in the essay, Nietzsche also considers artists and women; I will deal with neither here.

“precisely because it was the dominating instinct whose demands prevailed against those of all the other instincts…” (GM, III, 8)

GM III 10.

GM III 7.

“the philosopher sees in (the ascetic ideal) an optimum condition for the highest and boldest spirituality and smiles – he does not deny ‘existence,’ he rather affirms his existence and only his existence…” (GM, III, 7) and “We have seen how a certain asceticism, a severe and cheerful continent with the best will, belongs to the most favourable conditions of supreme spirituality, and is also among its most natural consequences: hence it need be no matter for surprise that philosophers have always discussed the ascetic ideal with a certain fondness.” (GM III 9)

See GM, III, 9, 10 on this point, and GS 3, 4, 19.

I suppose there are some who think that asceticism is merely a way of seeing more “clearly” what is already there, but I will not address such views here.

Regardless of the issues I have with Evola’s philosophy, I find his descriptions of asceticism to be among the clearest. This stuff is taken from his The Doctrine of Awakening.

Nietzsche sometimes speaks like this too. In Ecce Homo there is a famous passage where he says to something of the effect that “to become oneself one cannot have the faintest idea of what one is.” In this sense, his views could also be lumped in with this category. These things are very complicated, and oftne when I think I’ve found something that is inconsistent with Nietzsche a friend of mine will show me a passage where he has effectively the same idea cast in different terms. It’s part of what makes him hard to critique and why, I think, the whole idea of critiquing him is rather unimportant. With that said, I do think that genuine ascesis would make little sense to Nietzsche, who had no conception of a “spiritual” instinct beyond mere life as well have seen, just as Schopenhauer had no concept of a “spiritual will.”

While this might sound weird, it really isn’t. It is rather uncontroversial that happiness is something that cannot be intended either. For deeper emotions like bliss and serenity, this is even more true. This is one of the Buddha’s great philosophical insights.

Even Cicero, in The Dream of Scipio, gives us an example of this kind of thinking, though it is unclear whether Cicero himself takes it seriously or not.

None of this is original in the slightest. One can consult any number of thinkers who deal with this kind of theme. Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung are two common ones today, though their description of the process is often more psychological.

Junger’s War as Inner Experience is a good expression of this idea.

Islam actually makes the distinction between the lesser and greater war. The lesser, exoteric war is between the man and the “infidels” whereas the greater one, the “holy war” is an inner struggle against cowardice, fear, passivity.

This is worth noting given the fact that Nietzsche took endings to be of especial importance: “Masters of the first form may be recognized by the fact that they know how to end things in the perfect manner.” (GS, 281) Thank you to Colton for bringing my attention to this fact.

“Whenever the hero appeared on stage, something new was achieved, the thrilling counterpart of laughter, the profound shock of many individuals at the thought: “Yes, life is worth living! I am worthy of living! Life and oyu and I and all of us together once again became interesting to us for a time.” (GS, 1)

If anybody knows a passage on this please comment or DM me.

It is an interesting etymological fact that the word “human” goes back to the Latin “humanus” which means “of man” or perhaps “belonging to man.” The point being that the “man” here is conceived not as an organism of a particular psychophysical structure but of something altogether greater (man) which “takes possession” of the human being.

I have never met a woman who understands heroism of this kind. But, on the flip side, women seem to have their own unique species of “heroic” acts that pertain to motherhood. The difference is that the woman will sacrifice everything for her child (or man?). This is a very complicated question, however.

This need not necessarily constitute a perverse distortion of life and could well be its terminus. This was actually similar to the view of Aristotle, whose God moved the world not through mechanistic causes but through desire, which could even be conceived as an instinct in a Nietzschean scheme. The claim that this kind of teleology reduces existence to a fixed point is also an error, for Aristotle clearly distinguishes between two kinds of action: kinesis and energiea. The former has a definite end which once accomplished finishes the act; the latter exists in a state of perfect actuality and has no end.

This seems quite similar to certain strains of alchemist thought where the “alchemical gold” is buried in the “earth” and must be purified.

When Levels first came out, it was thought by some that Plessner was developing Scheler’s ideas because Scheler was more famous.

If anyone knows more books on this subject, please comment or DM me.

Thanks of the thoughtful comment. I actually think “heroism” is much more complicated and involves concepts like “play” and even a relation to others. But I do think there is a connection between heroism and asceticism. I’ll try to treat these in more detail elsewhere. Initially this began as an attempt to show, in very clear terms, a way of breaking with N that doesn’t fall prey to his most obvious attacks.

I tend to agree with your thought at the end, too. As I see it, N was correct to champion vital values but wrong to think they are the highest.

And here I was thinking tapas were delicious appetizers. I learned a lot today!